Rtfobj

Set RTFObj = Nothing Set RTFObjs = Nothing Set fso = Nothing ActivateScreen 'TRENDSCREEN',0 'Update trend view data by re-calling screen Last edited by: McAndrew at: 01:19:18. Title: Analyzing Malicious Documents - Cheat Sheet Author: Lenny Zeltser (www.zeltser.com) Created Date: 1:12:14 PM.

ThisIsSecurityIntroduction

Information stealer malware are used on a daily basis by cyber-criminals. They are often designed to extract saved password stored within browsers, instant messaging applications, FTP clients and many more. Key-logger mechanism may also be embedded, in order to grab additional credentials, that are never saved on the file-system.

In this blog-post, we will explain how we caught a recent sample of Agent Tesla, a .NET information stealer, dropped by a word document exploiting CVE-2017-0199. Then, we will describe the obfuscation layers used to delay the reverse-engineering process. Finally, we will explain few recent features involved with this malware, and we will talk about which targets it successfully compromised.

A word document exploiting CVE-2017-0199

We caught this malware thanks to Breach Fighter, our cloud-based sand-boxing engine, used to analyze files received by our customers.

The initial infection vector was an Open XML Microsoft Office Word Document (RFQ REF NS326413122017.docx), sent by email the 18th December 2017. This document exploits the CVE-2017-0199, in a way similar to the sample which led to the original disclosure of this vulnerability.

An OLE object is used to retrieve a RTF document (u2qe.doc) from an external source, using HTTPS:

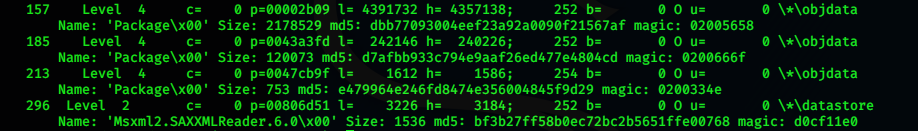

Using rtfobj, the RTF file can be analyzed, and its embedded OLE link object can be extracted. Using oletimes, one can see the OLE link object’s metadata:

Interestingly, the OLE object is supposed to have been created the 14th April 2017, 8 months before being sent by email. By taking a closer look, it can be deduced that this document has actually been created using the same OLE object as the one used within the metasploit module, office_word_hta, which contains this hard-coded modification time.

Using olebrowse, one can see the URI related to the OLE link object:

This URI leads to an HTA file, used to download and start a Windows executable (dferfgwergca.exe), using the class System.Net.WebClient and the powershell cmdlet Start-Process. This executable is described in the following section.

Agent Tesla – 3 stages to the final payload

The malware is composed of 3 stages, all written in .NET (C#), where each stage contains the PE image of the next stage, often as an obfuscated or encrypted resource:

In the following sections, we will explain how to extract the PE image of each stage, to obtain the final payload of Agent Telsa. In the last section, you will find the IOCs related to this sample.

Stage 1 – Obfuscated code and a resources

The first stage (dferfgwergca.exe) is the PE downloaded by the RTF document, through the HTA script. It is a quite big executable of more than 1MB, composed of 65 encrypted resources, for a total resource size of 937KB. Each resource’s name is composed of random Chinese characters:

This .NET executable has been obfuscated by a tool which implements several obfuscation tricks such as symbol renaming, control flow flattening and usage of .NET reflection. Thus, the code decompiled by dnSpy can’t be easily understood:

Rtfobj.py

Unfortunately, the obfuscator is unknown to de4dot, though symbol renaming can still be applied to replace these annoying unprintable unicode characters. By using dynamic analysis, it can be drawn that an array of 62 strings is built, where each string is a resource identifier which identifies an encrypted chunk of the 2nd stage’s PE image. Then, an instance of the class System.Resources.ResourceManager is created in order to access and concatenate these 62 pieces of chunk and rebuild the encrypted PE. Finally, an instance of the class System.Security.Cryptography.RijndaelManaged is created, and the PE is decrypted using the following AES parameters:

- Cipher mode: CBC

- Block size: 16 bytes

- Padding mode: PKCS7

- IV: 3F00FF056F2AD5CB71AECB92938A65EF

- Key: 29E18312D0AC9BC9FB7279872652368F054FE4A18A0EBA5306210417692FD225

After decryption, one can see the MZ signature of the PE file, used as the 2nd stage. This buffer can be dumped as it is, to obtain a valid PE file:

Stage 2 – A dropper also used by Recam

The second stage (stub.exe) is still a quite big executable of 927 KB, that looks like being obfuscated with ConfuserEx. Even though the obfuscator prevents decompilation, some symbols haven’t been renamed:

It is interesting to point out that this executable seems to be the same dropper as the one used by Recam, another information stealer malware, as shown by Talos in this article. Indeed, one can find the exact same methods in Recam’s dropper module.

However, by looking to the configuration of this dropper, within the resources, one can notice few differences with Recam’s dropper configuration:

- This dropper uses injection type ‘Reflection’ (6), rather injection type ‘Browser’ (5), which consisted into using the RunPE method for injecting itself within the default browser. Please note that the DLL ‘RunPEDll.dll’ is still embedded within the resources, though it isn’t used. At the time of writing, this DLL it is still unknown on VT

- This dropper doesn’t use LZMA compression to extract the embedded PE

- This dropper doesn’t use anti-dump protection, neither any persistence startup method (persistence is ensured by the stage3 itself)

- This dropper includes a resource named ‘PUMP’, of exactly 600KB, that doesn’t seem to be used

Since the embedded PE isn’t compressed with one of the 2 methods supported by this dropper (LZMA and GZIP), it can simply be extracted from the resources, as it is.

Stage 3 – The Agent Tesla malware

The third stage (ptm.exe) is the final payload, the Agent Tesla malware. It is a well-known information stealer malware, that even has an official website, used as a marketing platform in order to sell the malware, highlight its features, provide a detailed change-log about new releases, and so on.

Few months ago, Fortinet analyzed a sample of this malware, where the delivery method and .NET executable used to protect the final payload were different. In their article, they described the overall behavior of the final stage, including:

- The commands sent to the C&C server

- The key-logger and screenshot mechanism

- The targeted installed software

- Unused other features such as SMTP as a potential communication method

By briefly analyzing this sample, we noticed few differences that will be described in the following sections.

Decrypting malware’s strings

Such as Fortinet’s sample, this one uses string encryption to hide its malicious intent and complicate the reverse-engineering process. String encryption is performed using AES in CBC mode, with a key derived from a random password using SHA-1 with 2 iterations. In order to simplify analysis, we wrote a small plugin for DNSD (Dot Net String Decoder), in order to rebuild this sample, with calls to the string desobfuscation function replaced by references to decrypted string:

HTTP payload encryption

In the previous version of Agent Tesla, HTTP requests directed to the C&C server were made without encryption, as it can been seen on this screenshot. In this sample, a dedicated function is used to encrypt the keys/values parameter string, using 3-DES in CBC mode. The resulting encrypted buffer is then encoded in base 64, and used as the value of an application/x-www-form-urlencoded parameter whose key is ‘p’. Here is the function used to encrypt the keys/values parameter string:

It’s not really a surprise seeing HTTP payload being encrypted, since it was announced on Agent Tesla’s website with the version released the 09th October 2017:

However, the User-Agent hasn’t changed and is still hardcoded with the following value:

Rtfobj Install

Although all the code related to HTTP C&C communication is embedded within the sample, it isn’t used.

Using SMTP as an communication mechanism

Fortinet identified in their sample that SMTP could be used to communicate with the server instead of HTTP, but this feature wasn’t used yet. In this sample, SMTP is indeed used rather than HTTP. By analyzing this sample, we retrieved the credentials used by the malware to authenticate itself to the SMTP server, in order to send e-mail containing data gathered from infected computers:

Ironically, the actor behind this instance of Agent Tesla used the same email address for the originator (MAIL FROM) and the receiver (RCPT TO). We think that he simply registered an e-mail account on hostgator.com, in order to forward incoming e-mails to another e-mail address. Please note that sometimes, attackers use compromised SMTP credentials, and don’t always register a dedicated account. Using public malware analysis sandboxing websites, we found several samples of Agent Telsa, which used compromised SMTP accounts.

Analyzing the mail campaign

We found that 4255 e-mails, coming from 154 unique infected IP addresses, have been sent to the email account owned by the attacker. Please note that within this set of e-mails, some may have been sent by malware analysis sandboxing platforms. It is interesting to point out that the United Arab Emirates is the state which has been the most targeted by this threat, with 30.5% of unique infected IP addresses:

As you can see, the higher count of compromised IP addresses, at the same time, has been reached the day when the attacker sent the email, the 18th December 2017:

Based on this graph, we can think that a first (smaller) mail campaign started between the 8th and 9th December 2017. The fast decrease of infected computers’ count can probably be explained by the fact that, at first, Anti-viruses didn’t block this threat, but deployed an appropriate signature quickly. While a fast response to this kind of threat may seem reassuring, a single execution of few seconds is enough to extract and send saved passwords to the attacker. This illustrates that by using several obfuscation layers, attackers remain one step ahead of the anti-virus industry.

Yara rule

Edit: Here is a Yara rule which can be used to detect the last stage of Agent Tesla. It is interesting to point out that, unlike many others strings of this malware, a few ones are not encrypted.

IOCs